Boards Should Anticipate ‘The Blame Game’ •

By Michael Peregrine •

There’s a lot of discussion these days about preparedness. Preparedness for the pandemic, preparedness for the recession, preparedness for the unknown and the unthinkable. And there’s a lot of discussion about blame as well. They should have seen it coming, they should have seen the signs, they should have had a plan.

Now some of this discussion is totally unfair. The very nature of “black swans” is that they’re not really foreseeable. But some of this discussion is, unfortunately, quite fair; that with a little imagination the otherwise unpredictable can be anticipated. A sense of accountability seems to be in the air—for the virus, for the displacement, for the uncertainty and for the scarcity of toilet paper. There will be consequences for the failure to be prepared, regardless of whether those consequences may seem justified.

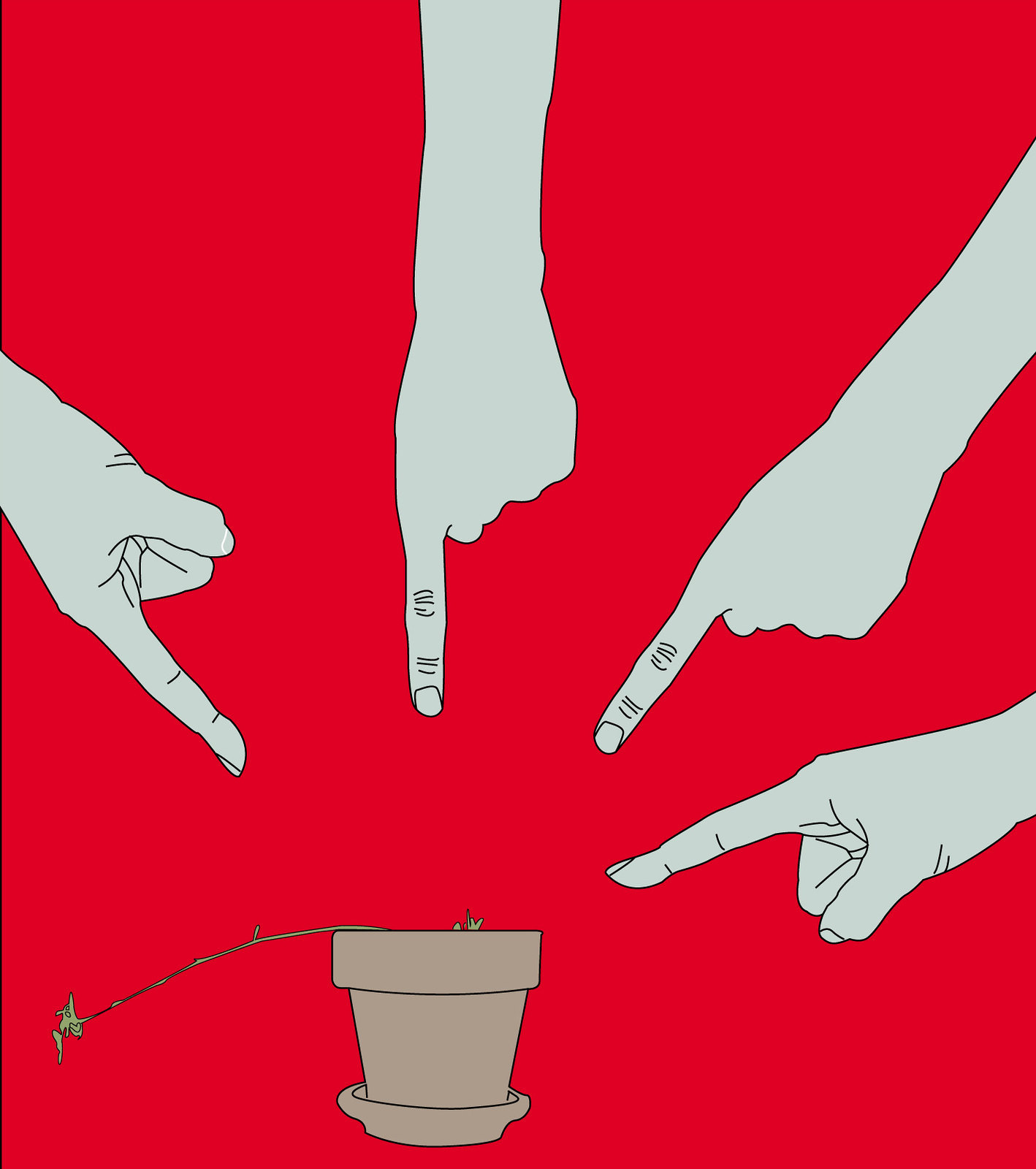

And those consequences may ultimately trickle down to corporate boards. For when blame becomes the national order of the day, leadership of all institutions is exposed—fairly or not. As the practice of hindsight becomes emboldened, the “enterprise risk” preparedness of governance may be subjected to a more rigorous scrutiny that is less forgiving than what the law currently requires. You missed the warning signs of enterprise peril and the company now suffers for it. Boards are well advised to anticipate this trend, and plan for it. Preparedness again.

The consequences of “the blame game” may be felt by boards in two different ways.

First, it may accelerate the recent willingness of the Delaware courts to move away from their long-held, director-friendly standard of conduct for board risk oversight duty. This standard requires allegations of bad faith to support a claim for breach of that duty by a director. It’s a standard that (at least before the pandemic) was regarded as “possibly the most difficult theory in corporate law upon which a plaintiff might hope to win a judgment.”

However, two prominent Delaware decisions in 2019 allowed a breach of oversight duty action to proceed based on allegations that the board missed, or misinterpreted, significant “red flags” of compliance problems. The fact that a compliance plan was in place for each company wasn’t enough to provide a defense for the board—as it might have been in prior times. (Notably, one of the cases involved a listeria outbreak in the company’s manufacturing process.) The concern is that in an “atmosphere of accountability”, this trend will continue—especially with respect to allegations that implicate director oversight of matters of public health and safety and/ or consumer rights and interests.

Second, it may recast how the board approaches its enterprise risk evaluation. Not just as to the traditional enterprise risks such as business disruption, workforce turmoil and supply chain breakdown. But especially as to those risks that are existential in nature, e.g. global economic depression, national political upheaval, environmental/climate change disasters and —oh yes—public health catastrophes. These are the “black swan” incidents or Donald Rumsfeld’s “known unknowns and unknown unknowns.” All are well described by National Association of Corporate Directors risk-oriented publications.

As uncertain as these may be, the failure to acknowledge them may henceforth attract the sharpest finger pointing. Just how seriously have boards taken these risks, existential or otherwise? Evaluated them and possibly adopted a plan to prepare for them? To mitigate “blame game” concerns and to prepare for the next crisis, boards may consider the following steps.

1. Reinforce Risk/Compliance Staff. Work with management to add skilled personnel to the company’s existing risk management and corporate compliance teams; increase horizontal communications among officers with risk-related responsibilities and enhance the quality of vertical reporting to the board and key committees.

2. Board Composition. Reconsider the extent to which the director selection process focuses on specific competencies, rather than a broader diversity of experience and background. Evaluate the individual qualities that are best suited to identify and address existential enterprise risk.

3. Overboarding. Give closer consideration to expectations of director time commitment to this particular board. (Engagement is always a factor courts and regulators consider when evaluating risk response). Implement limitations on outside board service that are intended to support director engagement with the company’s risk challenges.

4. Committee Structure. Re-evaluate whether the existing committee structure is sufficient to provide effective oversight of the enterprise risk and its key elements (e.g., legal, risk management, corporate compliance, etc.) and make changes as necessary (e.g., don’t be afraid to add to, or restructure existing, committees).

5. Director Retention. An atmosphere of accountability will require greater organizational effort to train, support, insure and compensate board members who might otherwise be anxious about their personal liability profile.

6. Culture of Imagination. Particularly important will be inculcating a culture of reasoned imagination into the risk oversight process, supporting the ability of board members to think broadly in their analysis of risk.

This is especially the case as to “black swan” events and “known unknowns and unknown unknowns”. It’s the creativity to look around the next corner, look beyond the horizon, and to think above and beyond the traditional scope, for warning signs of future great crisis. To paraphrase former NASA officials, this new culture involves directors using their imagination to envision what can go wrong.

But essentially directing board members to hunt for sources of potential catastrophe may be a challenge to executive leadership. OK, tell me how that’s not going to be a distraction? But if COVID-19 teaches us anything, it’s that the unimaginable can happen; and that such events are often preceded well in advance by warning signs that the truly attentive will recognize and plan for. Preparedness once again.

The process of corporate governance can expect to be caught in the prop-wash of COVID-19 accountability. There’s likely to be a great national need to project blame for a perceived lack of institutional preparedness. And this may have a trickledown effect on the evaluation of director conduct as it relates to the oversight of risk. But that’s something for which boards can readily prepare-and they would do well to start doing so.

Michael Peregrine is a partner in the Chicago office of international law firm McDermott Will & Emery.