At companies of almost all sizes, across all sectors, boards are undergoing a profound transformation. Largely as a result of intensifying shareholder intolerance of mediocre or poor corporate performance, the ceremonial boards of the past are being replaced by active boards that are more demanding of managers and more intrusive in their affairs.

This change can be daunting and frustrating for CEOs. However, based on our experience of advising CEOs, operating as CEOs, and sitting on boards, we have found that executives can be effective in the new environment by revamping their interactions with their boards. It consists of four approaches.

Work with board members individually as well as in the group — and selectively seek their help. It’s remarkable how many CEOs focus mainly on formal boardroom relationships. Yet by investing the time in regular one-to-one informal interactions, a CEO will help address the new active board members’ sense of duty to get close to the business. Through a personal dialogue, the CEO can better enlist them in important initiatives and address issues before they become crises. In addition, by creating a personal bond with the individual directors, the CEO lessens the odds that they will undermine or blindside him.

It is especially important to create a bond with the lead director and/or the chair. As boards have become more active, the lead director and board chair hold the keys to setting productive agendas and managing issues with the total board or individual members. One of us served on an active board that included members who frequently threatened to derail agendas and process with counterproductive questions. The CEO quietly recruited the lead director and chair to restore order, which they did. As boards have become more active, the lead director and board chair hold the keys to setting productive agendas and managing issues with the total board or individual members.

CEOs should consider recruiting one board member as an informal advisor. This must be done with great care and an ear for political nuances. For example, as one CEO we know discovered, a prospective board advisor actually had his eye on the CEO role for himself — hardly the right confidant! By using already-scheduled one-on-ones to assess board members for this advisory role, the CEO can better identify an appropriate advisory board member. This board member can be of great value as a sounding board and a guide to working effectively with the rest of the board.

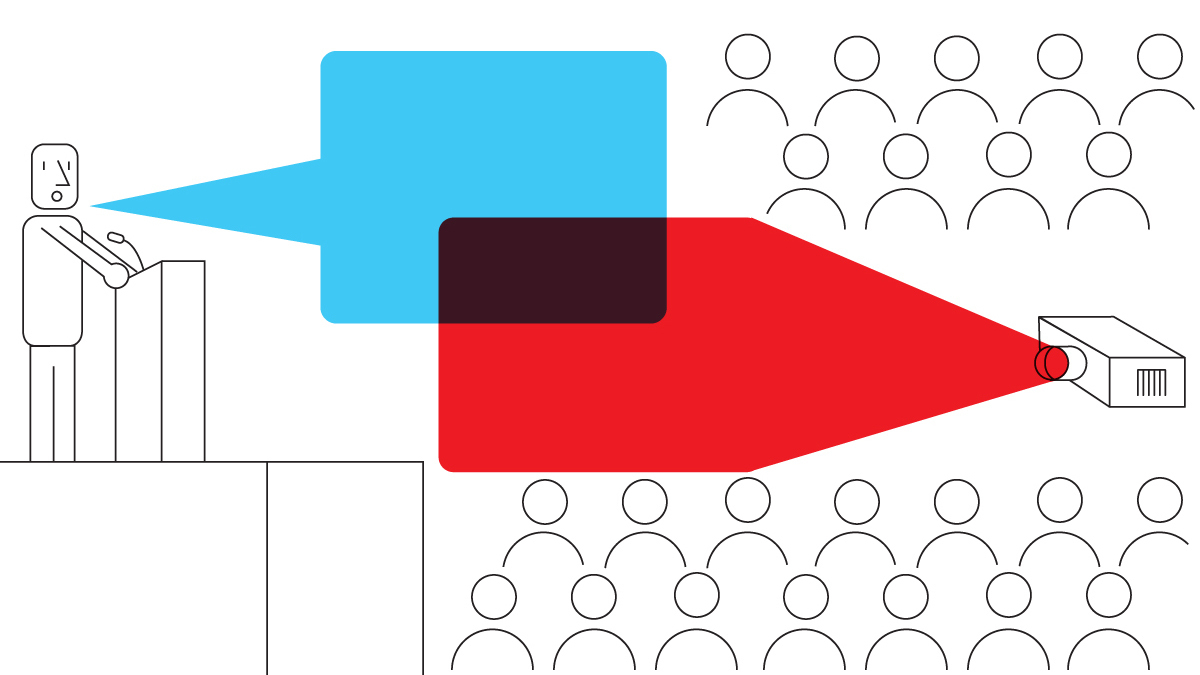

Communicate less formally, more intensively, more often. Many CEOs and their teams still deliver traditional 80-slide PowerPoint summary presentations at board meetings. But given that today’s boards increasingly want a substantive dialogue, we advise replacing the presentation with a thoughtful, verbal review and Q&A around critical updates, challenges, and opportunities. (Further background can be provided in brief pre-reading material.)

This will show that the CEO is using his or her face-to-face time with the board for serious discussion. It will focus board activism on topics where the CEO will benefit from directors’ insight and counsel. And by taking the lead in inviting the board to engage on business-critical matters, the CEO can better manage the process and avoid one of the biggest downsides of the active board: disruptive interference by board members in business operations.

It may seem obvious that CEOs should communicate with board members regularly and substantively between board meetings. But in reality, CEOs often communicate mainly when there is a problem. Many also have difficulty regularly addressing a balanced mix of important topics.

One very effective approach to this issue is regular CEO letters to the board. The management of this letter should be delegated to a top lieutenant such as the head of communications or the COO. A monthly rhythm has proven effective with many boards. To assure balanced, relevant content, the letter should routinely address a fixed set of regular topics (e.g., business-environment trends, business updates, people/talent news, and early warnings of potential upside and downside developments).

Expose Level 3 and 4 managers to the board. While boards in the past were typically focused on CEO succession planning and the talent among the CEO’s direct reports, active boards are also very interested in the levels below. They rightly see these executives as the future leaders and the operational leaders of today who should be driving performance. Active board members will therefore seek to get to know them.

Some CEOs feel this is overly intrusive or worry that the lower-level executives are not ready for board exposure. But, in fact, it’s positive to have board members engaging with deeper levels of talent. They learn more about the business and the next generation of the company’s leaders. Board members can also give the CEO valuable feedback about the people they meet and their view of the company’s overall bench strength. And for the executives, the right kind of exposure to board members is a great development opportunity.

The CEO should take the lead with the board in driving the engagement process, which will allow him or her to have greater influence over it. She can select the highest potential individuals for the interactions and organize the interactions so that they are most productive — for example, by holding them as one-to-ones over a breakfast or dinner. She can also brief the executives in advance on the style of the board member and potential question areas and brief the board members on the executives they will meet.

Handle strategic planning… strategically. Older-style boards typically become involved only at the end of the strategic-planning process — typically in a board meeting devoted to review and approval of the strategy. By contrast, active boards often push to be involved from the start because the strategy is so important to the company’s performance.

The notion of involving the board in strategic planning can make CEOs anxious and defensive. They fear that the board may undermine the planning process due to insufficient knowledge about the business. They also worry that board involvement in strategic planning will be the thin edge of a wedge and lead to board interference in day-to-day management of the company.

The key to navigating this challenge is to keep strategic planning in the hands of management but to invite the board to provide advice and feedback from the beginning. One good way to do this is to involve the board early in deciding on the right, big-picture, strategic direction for the company, without getting into the details. The CEO and her team can develop and present to the board several options to the board, explaining why each has merit. Then the executives can solicit board input on each but not ask for a vote. In this way, the CEO and her team can gain valuable board perspective that will strengthen all the choices that are developed and obtain early board buy-in for both the options and the ultimate strategic plan that’s chosen.

The CEO can then provide periodic updates on the strategic-planning process through letters to the board and board meetings. This allows the board to stay engaged and provide input but keeps the control over the actual process with the executive team, where it belongs.

***

Active boards are a corporate reality. How to work with them effectively should be one of the most important items on the CEO agenda. As we have outlined, the CEO has an opportunity not only to manage this new relationship but also to make the active board an asset in building long-term, high performance of the company.

By Ken Banta & Stephen D. Garrow

Source and in HBR's 10 Must Reads for CEOs